In a previous post, I use a similar script to calculate NDVI per polygon. However, this script includes a small difference which I have not yet myself understood why it was necessary.

As before, my shapefile consists of the administrative borders of Tanzania. I got this shapefile from the GADM database (version 3.6).

// Import administrative borders and select the gadm level

// (0=country, 1=region, 2=district, 3=ward)

var gadm_level = '2';

var fc_oldID = ee.FeatureCollection('users/username/gadm36_TZA_'+gadm_level);

Map.addLayer(fc, {}, 'gadm TZA');

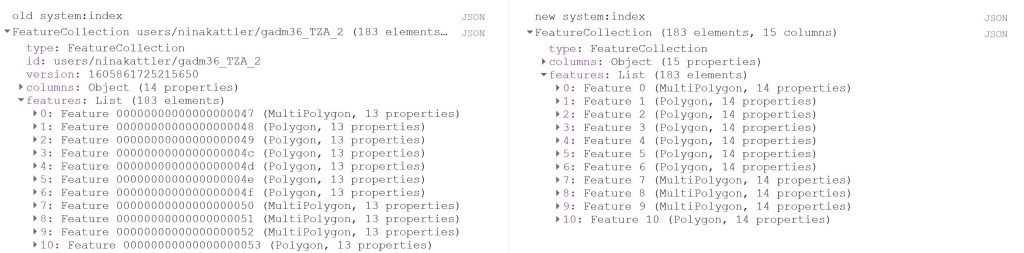

Map.centerObject(fc, 6);Now I change the system:index of the FeatureCollection.

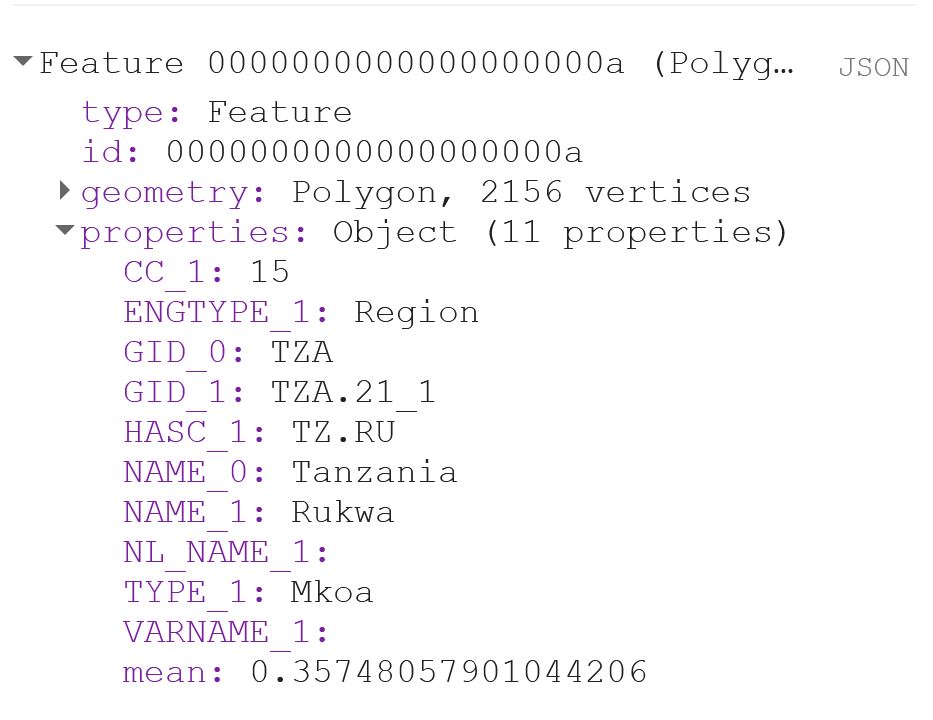

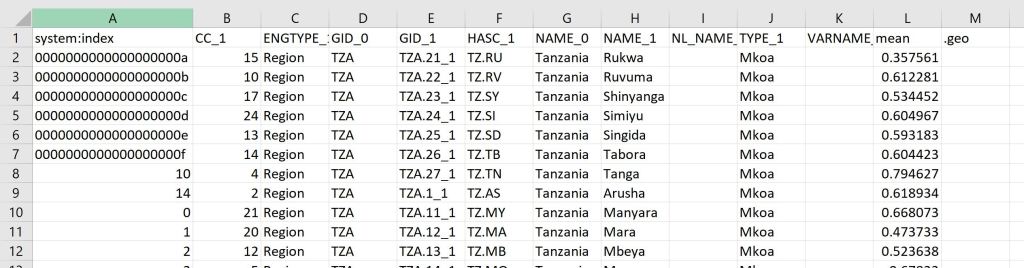

Why do this at all? I was struggling to produce a mean value of the COPERNICUS landcover data, after having created a successful script for the MODIS NDVI dataset. When I ran the script, no mean column was created. However, I was able to calculate mean values from a couple of polygons that I created myself within Google Earth Engine, so I knew the problem had to be in the shapefile somehow. So I started to investigate the gadm asset (i.e. the shapefile) and saw that Google Earth Engine automatically assigns some odd index names to each feature (e.g. 000000000001 or 0000000000a). I used the following steps described by the user Kuik on StackExchange to change the system:index:

// Change the system:index ("ID")

var idList = ee.List.sequence(0,fc_oldID.size().subtract(1));

var list = fc_oldID.toList(fc_oldID.size());

var fc = ee.FeatureCollection(idList.map(function(newSysIndex){

var feat = ee.Feature(list.get(newSysIndex));

var indexString = ee.Number(newSysIndex).format('%01d');

return feat.set('system:index', indexString, 'ID', indexString);

}));

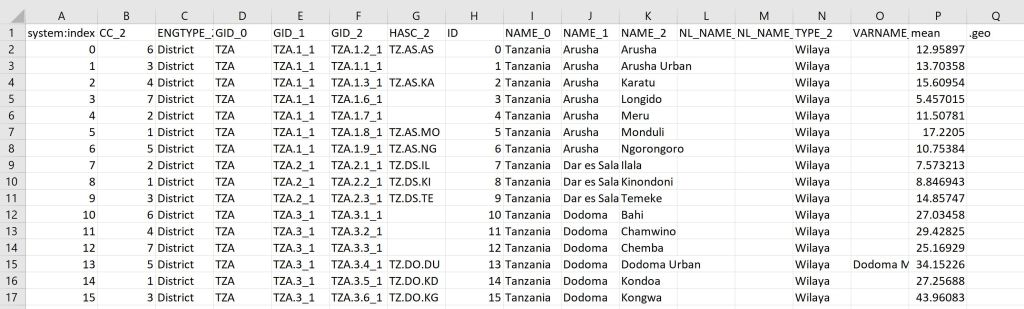

print('new system:index', fc);Now you can see that the system:index has been changed:

Now I load in the landcover data. Here I use the 100m resolution, yearly Copernicus Global Land Cover dataset. Here we can find an image per year from 2015-2019. This dataset has a long list of interesting bands, e.g. a land cover classification with 23 categories, percentage of urban areas and percentage of cropland. In this script, I will look at the percentage of cropland (crops-coverfraction) for different administrative regions in Tanzania. Read more about the COPERNICUS dataset here.

// Load data

var year = '2015'

var lc = ee.Image("COPERNICUS/Landcover/100m/Proba-V-C3/Global/"+year)

.select('crops-coverfraction')

.clip(fc)

print('Image from '+year, lc)

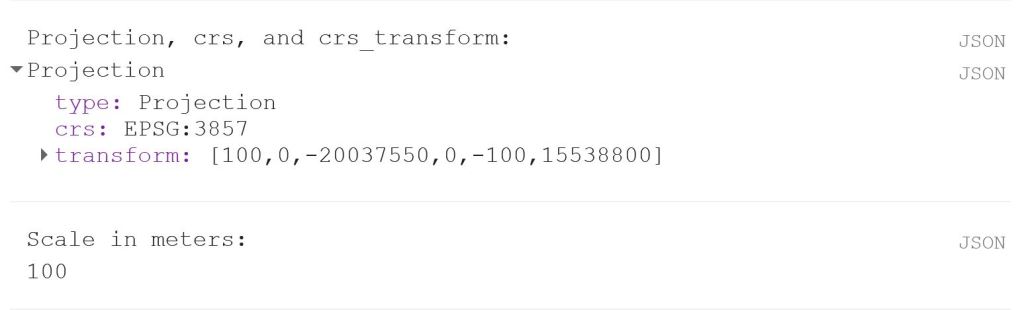

print('Projection, crs, and crs_transform:', lc.projection());

print('Scale in meters:', lc.projection().nominalScale());The last two lines is a good way to get a bit more information about your data if you, like I was, are looking for a reason why your script is misbehaving. It will give you the following output:

Now we can use the reducer reduceRegions. Again, remember that the scale should reflect the spatial resolution of the data. In the image above, we can see that the scale is 100 m.

// Reduce regions

var MeansOfFeatures= lc.reduceRegions({

reducer: ee.Reducer.mean(),

collection: fc,

scale: 100,

})

print('gadm mean', ee.Feature(mean.first())) // Test if mean is produced

// Set visualization parameters

var lcVis = {

min: 0.0,

max: 100.0,

palette: [

'ffffff', 'fcd163', '99b718', '66a000', '3e8601', '207401', '056201',

'004c00', '011301'

],

};

Map.addLayer(lc, lcVis, 'crop cover (%) '+year)

// Export the featureCollection (table) as a CSV file

Export.table.toDrive({

collection: MeansOfFeatures,

description: 'proba_V_C3_TZA_adm'+gadm_level+'_'+year,

folder: 'GEE output',

fileFormat: 'CSV'

});This should give you the following output:

You can find the full script here.