At my work, we have a lot with sensors installed all over the city, which take measurements at certain intervals, e.g. once per minute. For example, a water sensor, which every minute measures the current level of rain water in an underground basin.

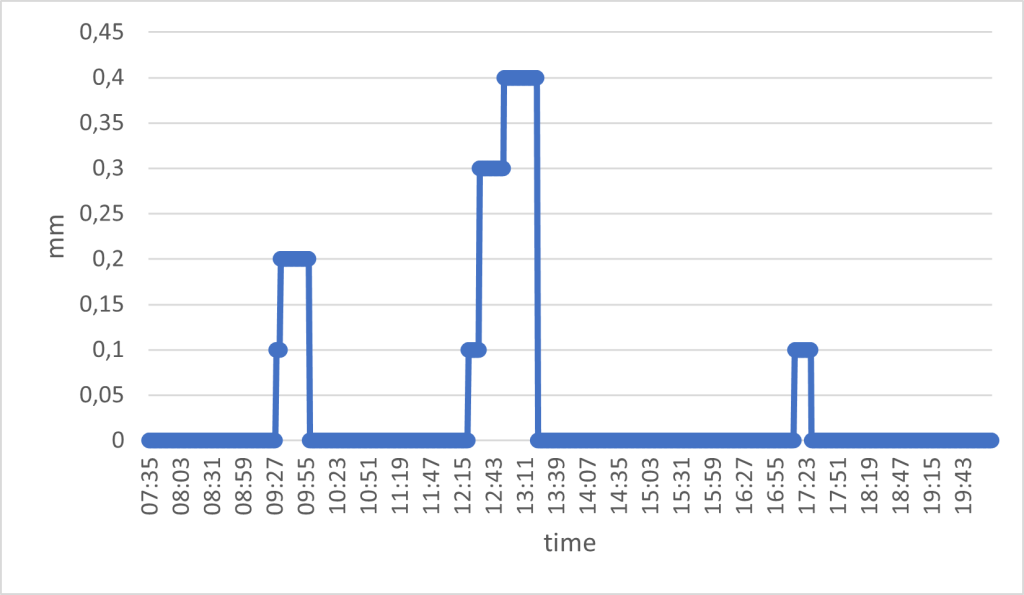

Most of the time the sensor will measure zero amount of water. So our dataset can look something like this, during a day with a couple of showers:

The water sensor works as a tipping bucket; it reports the amount of water in the bucket, and after a while it will empty the bucket. This means that the mm of water represents the total, accumulated amount of water in the bucket. As such, you will never see the amount decreasing; it will go from the max value to zero.

I am interested in understanding two things:

1. How many rain events occur per day

2. How much water is registered in each rain event

My data is stored in a PostgreSQL database (version 13). First, let’s define the data I have available:

| Column name | Data type |

| sensor_id | varchar |

| timestamp | timestamp |

| no_measurement | int |

| value | numeric |

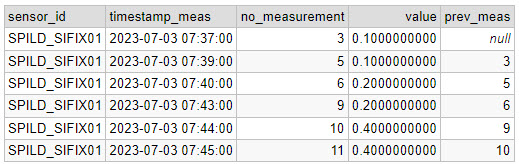

Here’s an example of what the data can look like:

| sensor_id | timestamp | no_measurement | value |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:35:00.000 | 1 | 0 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:36:00.000 | 2 | 0 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:37:00.000 | 3 | 0.1 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:38:00.000 | 4 | 0 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:39:00.000 | 5 | 0.1 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:40:00.000 | 6 | 0.2 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:41:00.000 | 7 | 0 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:42:00.000 | 8 | 0 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:43:00.000 | 9 | 0.2 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:44:00.000 | 10 | 0.4 |

| SPILD_SIFIX01 | 2023-07-03 07:45:00.000 | 11 | 0.4 |

The first problem I need to solve is how to isolate rain events and figure out if a rain event has occurred over multiple measurements (aka through time).

By removing the zeros, I get the rain events. But how do I figure out whether a rain event continues over multiple measurements? My solution is to use the LAG function. This function looks backwards 1 row (1 is the default, it can be set to any amount of rows) and gives you the value of that row for a specific column. I can use this function, because I am given a measurement count column (“no_measurement”). This means that any concurrent measurement will have a no_measurement value the same as the previous + 1.

For example, a rain event is recorded with no_measurement = 8. If this measurement is part of a continuing rain event, the previous measurement should have no_measurement = 7 if it is the same rain event.

SELECT *,

LAG(no_measurement) OVER(ORDER BY no_measurement) AS prev_meas

FROM MyTable

WHERE value!= 0::numeric

ORDER BY no_measurement

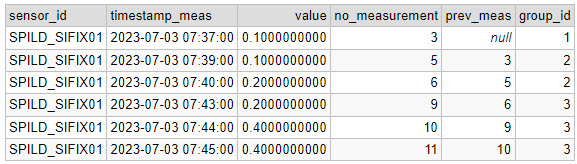

Now I have the expected previous no_measurement. Next step is to group the rain events (with a unique ID per group), by checking if the previous no_measurement fits with the current:

SELECT

sensor_id,

timestamp_meas,

value,

no_measurement,

prev_meas,

CASE WHEN m.prev_meas = no_measurement - 1 THEN currval('seq') ELSE nextval('seq') END AS group_id

FROM

(SELECT *,

LAG(no_measurement) OVER(ORDER BY no_measurement) AS prev_meas

FROM MyTable

WHERE value != 0::numeric

ORDER BY no_measurement) mNote that I am using a function called CURRVAL and NEXTVAL to give the groups a unique ID. I create a temporary sequence (called “seq”) from which I can get a unique ID using the CURRVAL/NEXTVAL. You create the sequence like this:

CREATE TEMPORARY SEQUENCE seq START 1;Now I have given the 3 rain events unique IDs:

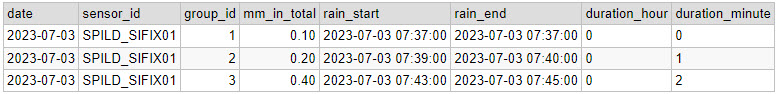

The final step is to use GROUP BY on the date, group_id, take the maximum measured value (because it is an accumulated value), add a start and end timestamp and calculate the duration of each event.

SELECT

DATE(timestamp_meas) AS date,

sensor_id,

group_id,

ROUND(MAX(value),2) AS mm_in_total,

MIN(timestamp_meas) rain_start,

MAX(timestamp_meas) rain_end,

(EXTRACT(HOUR FROM MAX(timestamp_meas))-EXTRACT(HOUR FROM MIN(timestamp_meas))) AS duration_hour,

(EXTRACT(MINUTE FROM MAX(timestamp_meas))-EXTRACT(MINUTE FROM MIN(timestamp_meas))) AS duration_minute

FROM (

SELECT

sensor_id,

timestamp_meas,

value,

no_measurement,

prev_meas,

CASE WHEN m.prev_meas = no_measurement - 1 THEN CURRVAL('seq') ELSE NEXTVAL('seq') END AS group_id

FROM

(SELECT *,

LAG(no_measurement) OVER(ORDER BY no_measurement) AS prev_meas

FROM MyTable

WHERE value != 0::numeric

ORDER BY no_measurement) m) t

GROUP BY DATE(timestamp_meas), sensor_id, group_id

ORDER BY group_id

Reflecting on this solution, this query could also have been written as a CTE (common table expression), which I think would have made the query more readable. Here’s a nice example of such a solution.